CNN vs. Vision Transformer: A Practitioner's Guide to Selecting the Right Model

Vision Transformers (ViTs) have become a popular model architecture in computer vision research, excelling in a variety of tasks and surpassing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) in most benchmarks. As practitioners, we often face the dilemma of choosing the right architecture for our projects. This blog post aims to provide guidelines for making an informed decision on when to use CNNs versus ViTs, backed by empirical evidence and practical considerations.

For those in a hurry, here is a decision tree to quickly choose between CNNs and ViTs for real-world projects. Alternatively, you can jump ahead to the conclusion for a list of practical recommendations.

This guide is primarily intended for practitioners and researchers in the field of computer vision who are interested in understanding the trade-offs between Convolutional Neural Nets and Vision Transformers for various applications. For the most part, I am assuming a background in machine learning concepts and familiarity with terminology related to deep learning architectures and training procedures. Also note that even though I have tried to synthesize some of the most relevant research here, I may have missed important insights that I should have incorporated. Please don’t hesitate to contact me if you spot any mistakes or things I missed!

Architectural Differences

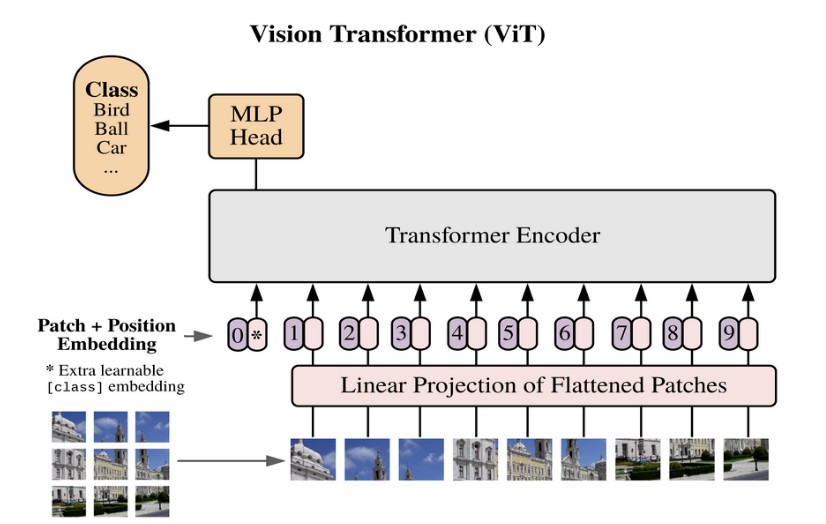

Let’s start with a brief comparison of the two architectures. I will explain only the essential information, as there are plenty of resources available to learn more about Vision Transformers (the original paper is a good start). Since the Vision Transformer architecture is largely identical to the original Transformer encoder architecture by Vaswani et al. (2017), I will use the terms Transformer and Vision Transformer interchangeably.

Transformers are flexible architectures with minimal inductive priors, meaning they make few assumptions about input data. In contrast, CNNs assume that nearby pixels are related (locality) and that different parts of an image are processed similarly (weight sharing). These assumptions, inherent to the convolution operator, help CNNs learn effectively with limited training data.

Transformers, on the other hand, have very few inductive biases. This means they have to learn more from the training data, thereby necessitating larger training datasets. They can outperform CNNs when trained on sufficient data, but struggle to learn meaningful representations with small datasets, underperforming other architectures (more on this later).

While CNNs start from the assumption that nearby pixels are related, the Vision Transformer makes no such assumption, considering the relationship of all pixels to each other with equal weight. This can lead to a better understanding of global relationships in an image, which a CNN might not capture because of its locality bias. Therefore, at a certain data threshold, inductive biases become a liability, rather than an asset. Transformers are highly scalable because they are minimally constrained by assumptions baked into the architecture.

Neural network architectures can be seen as existing on a spectrum of inductive biases, from weak to strong. ViTs occupy the lower end of the spectrum, while CNNs occupy the higher end. Depending on how well the inductive priors can be learned from the training data, one might choose an architecture with fewer or more inductive biases. For example, there are hybrid architectures which combine CNNs and ViTs into a single architecture. Such an architecture would sit in the middle of the inductive biases spectrum, with enough priors to avoid requiring a huge amount of training data, while still preserving some of the learning flexibility of the Transformer architecture.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that Transformers have had significant success due to self-supervised learning. This is a paradigm in which the model learns to extract meaningful representations from unlabeled data by solving pretext tasks such as predicting missing patches or identifying transformed images. Since Transformers are so data-hungry, self-supervised learning is an excellent way to scale up training datasets, as no labels are required. It leads to general-purpose representations that can be fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks with less labeled data. The most notable success stories are from NLP (e.g., BERT, GPT), but it is becoming increasingly common in computer vision as well. ViTs are the most common choice for self-supervised pretraining in computer vision (see, e.g., DINOv2, MAE), but CNNs can also be used.

In summary:

- Vision Transformers are highly scalable but require large datasets to learn effectively. They are most effective when scaled up to large sizes (or very large sizes). Self-supervised learning can enable such large-scale training, although supervised pretraining is also still quite common.

- CNNs have strong inductive biases (locality, weight sharing), allowing them to perform well with limited data. They are less scalable than ViTs, but outperform ViTs in smaller pretraining data regimes.

What does the research say?

Let’s now look at empirical studies studying and comparing CNNs and ViTs, to get an idea of their relative strengths and weaknesses.

I will note here that some head-to-head comparisons between CNNs and ViTs can be misleading, due to inconsistent comparison standards. Differences in model size, training dataset, augmentation strategies, and training length are all confounders that make a direct comparison difficult. For example, comparing a ResNet-50 to a ViT-B model (done here) is not a fair comparison, because the ViT-B model has 3.5x the number of parameters as the ResNet-50 model.

Data Requirements

Pretraining on ImageNet-1k has been standard practice for quite some time, typically followed by finetuning on a downstream task. Recent studies have shown the benefits of (supervised) pretraining on larger datasets than ImageNet-1k, such as ImageNet-21k and JFT-300M, even with noisier labels (Kolesnikov et al. 2019, Dosovitskiy et al. 2020, Steiner et al. 2021). This is true for both CNNs and ViTs, although CNNs such as ResNet require certain modifications, such as replacing batch normalization, in order to scale effectively (Kolesnikov et al. 2019). Thus, pretraining on more data is preferred for both ViT and CNN, even if the data is somewhat noisy.

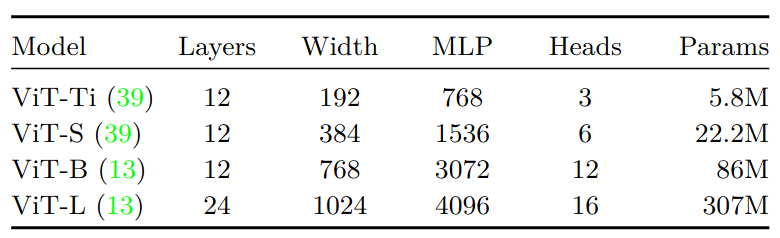

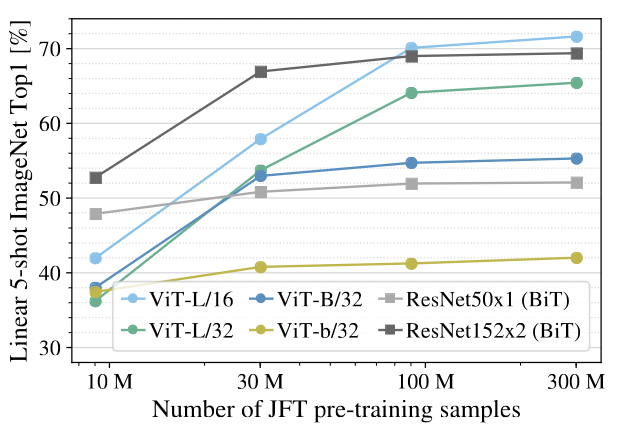

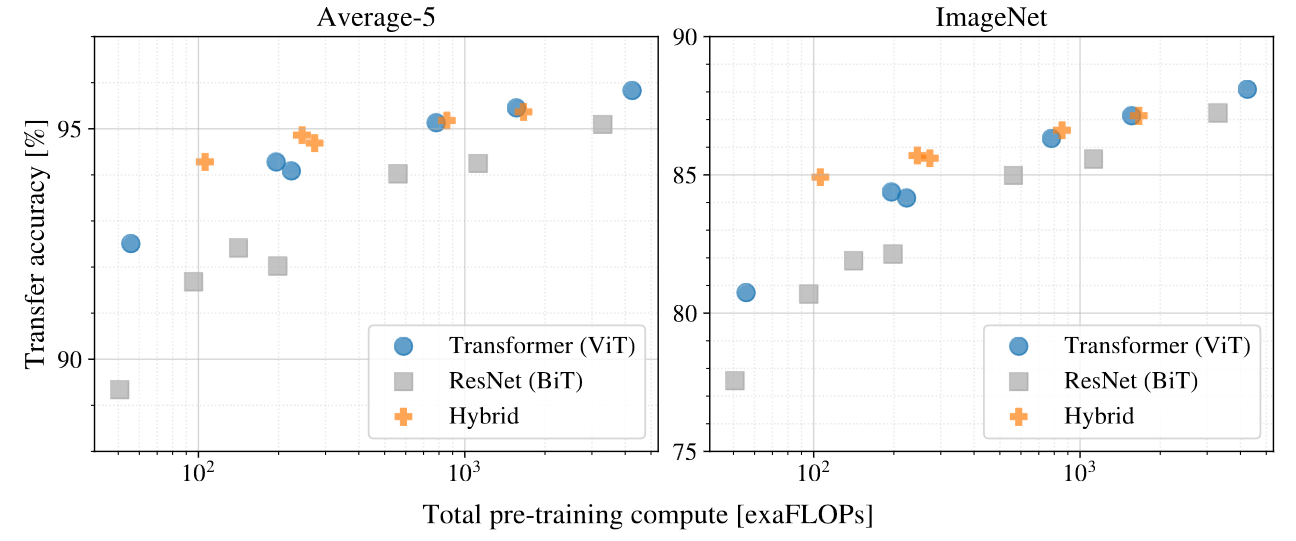

Dosovitskiy et al. (2020) compare the results of pretraining on progressively larger datasets: ImageNet-1k, ImageNet-21k and JFT-300M (1.3M, 14M, and 300M images, respectively), finding that ViTs underperform BiT ResNets (Kolesnikov et al. 2019) when trained on ImageNet-1k, but outperform BiT ResNets when trained on ImageNet-21k or JFT-300M. This can also be seen in the figure below (from the same paper), which shows ImageNet classification performance as a function of pretraining dataset size. ResNets perform better with smaller pretraining datasets but plateau sooner than ViT, which performs better with larger pretraining.

These results indicate that ViTs are more suitable for large-scale pretraining than ResNets, as their performance scales better on larger pretraining datasets. Although it is not entirely clear at which data scale ViTs start to surpass CNNs, I would put this threshold at about 10 million images for supervised pretraining (mostly based on the ImageNet-21k versus ImageNet-1k results).

In later studies, it has been shown that a ViT can be trained effectively on ImageNet-1k as well, using an improved training recipe with stronger data augmentation (Touvron et al. 2020, Steiner et al. 2021). ViT’s reliance on large datasets makes it benefit from stronger data augmentation during training compared to CNNs.

Transferability

Let’s now explore the transferability of CNNs and ViTs, i.e., how well their representations transfer to new domains. Transferability is a crucial factor for real-world applications, where compute and training data is often limited.

As discussed, ViTs require a large amount of pretraining data to show benefits compared to CNNs. One might conclude that without a massive training dataset, CNNs are the better option. However, in real-world projects, transfer learning — initializing a model from a pretrained checkpoint — is preferred over training from scratch. Even though some studies show limited benefits of transfer learning in rare situations (He et al. 2018), starting from a pretrained model almost never hurts. It usually provides faster convergence, better performance, and higher sample efficiency (see e.g. Kolesnikov et al. 2019, Steiner et al. 2021, Kornblith et al. 2018, Raghu et al. 2019). This is especially relevant since most popular models have pretrained checkpoints available, which should be used as initial weights for a model when starting any new computer vision project. For instance, Steiner et al. 2021 show that across a wide range of datasets, even if the downstream data of interest appears to be only weakly related to the data used for pretraining, transfer learning remains the best available option for training ViTs. Starting from a pretrained model should be the preferred choice 95% of the time, especially when working with small or mid-sized datasets. Training from scratch is rarely justified, requiring (1) a large domain gap between the pretraining and target task, and (2) a large amount of domain-specific data for (pre-)training.

This means that the decision between CNN and ViT should not necessarily be dictated by the size of the training dataset you have access to, but rather, the availability of a model checkpoint pretrained on a large dataset.

Let’s examine how well ViT and CNN representations transfer. The literature shows that pretraining on more data yields more generic ViT models that transfer better to various datasets (Steiner et al. 2021, Zhou et al. 2021). Furthermore, off-the-shelf ViT features transfer well to new domains, outperforming ResNets (Naseer et al. 2021). This makes a ViT pretrained on large amounts of data a good choice for transfer learning.

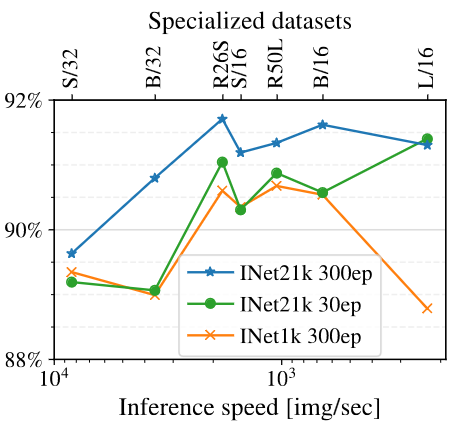

The plot below shows the transfer learning performance of ViT on the VTAB specialized benchmark, a suite of datasets consisting of medical and aerial images for classification, where each task contains only 800 training images. The plot shows that pretraining on more data is beneficial, as ImageNet-21k pretraining outperforms ImageNet-1k pretraining.

Pretraining performance correlates quite well with downstream finetuning performance for both CNNs and ViTs, with occasional exceptions. For example, weight decay and other regularizers can correlate negatively with pretraining performance but positively with downstream performance (Zhai et al. 2021, Kornblith et al. 2018). However, as a general heuristic for maximizing performance, starting from the model with the highest pretraining performance is most likely the best choice for transfer learning. Since the correlation between pretraining and finetuning performance is strong, but not 100%, then, if time or compute is not a limiting factor, one can try out several pretrained models to find the highest performing model for the downstream task.

Based on these findings, we can conclude that ViTs exhibit strong transfer learning performance, as is the case for CNNs. Compared to ResNets, ViTs appear to transfer better on average. In general, when pretraining data is limited, CNNs are most effective. As pretraining data is scaled up, there is reason to believe ViTs exhibit better transfer learning performance. However, there is also reason to believe CNNs can transfer equally well when using the same training tricks as ViTs.

Robustness

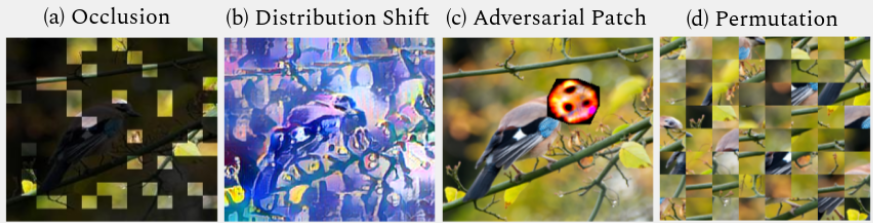

Having discussed transferability, let’s now examine the robustness of CNNs and ViTs. Robustness to image corruptions, such as those shown in the figure below, is particularly relevant when data drift is a concern in deployment settings.

There is evidence that ViTs are more robust to occlusions, adversarial and natural perturbations, and distribution shifts (Naseer et al. 2021, Paul et al. 2021, Xie et al 2021, Zhou et al. 2022, Shao et al. 2021, Zhang et al. 2021), with the self-attention architecture design playing an important role in achieving stronger generalization (Bai et al. 2021). On the other hand, the more recent ConvNeXt CNN architecture might achieve similar robustness to ViTs (Pinto et al. 2022).

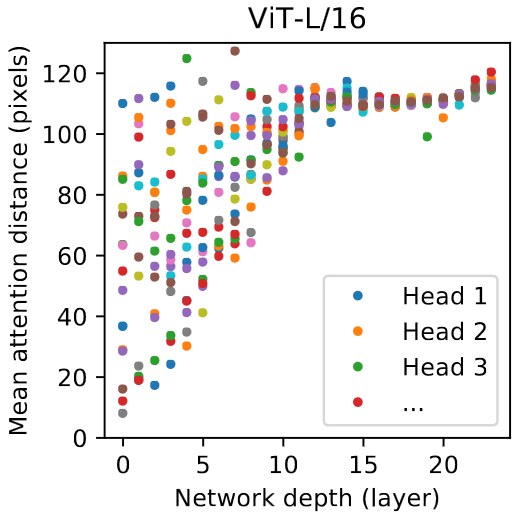

One explanation for the robustness of ViTs to corruptions such as occlusion is a higher bias towards shapes rather than local textures and backgrounds, compared to CNNs (Naseer et al. 2021, Zhang et al. 2021). This observation aligns well with the idea that self-attention more effectively captures global relationships, while convolutions are biased towards local interactions. While the receptive field of a CNN expands gradually with increasing depth, self-attention can flexibly adjust its receptive field as needed in any part of the network. For example, see the figure below, which shows that a ViT integrates information across the entire image even in the lowest layers.

Model Efficiency

Note: I realize this section could be supported with a bit more data. I might expand on it in the future.

Having examined robustness, let’s now consider the efficiency of CNNs and ViTs. Model efficiency is an important consideration, especially in applications where computational resources are limited. When it comes to model efficiency, several factors must be considered, such as FLOPs, power consumption, and memory consumption. Importantly, a distinction can be made between efficiency during model training and efficiency during inference (at deployment time).

When it comes to specialized architectures emphasizing model efficiency, CNNs are arguably more mature. For example, CNN architectures like MobileNet, SqueezeNet, and EfficientNet are designed to be lightweight and efficient, making them suitable for embedded or real-time applications. Additionally, there are various techniques to reduce model size and improve inference efficiency without significant performance loss, such as pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation. These techniques can be applied to both CNNs and ViTs. See also this paper for an interesting comparison of lightweight backbones (Table 3).

Dosovitskiy et al. 2020 show that ViTs are more sample efficient to train than ResNets when trained on the same computational budget (see figure below). ViTs use approximately 2-4× less compute to attain the same performance. This can be beneficial when pretraining on large datasets, as the model could converge faster.

Note also that due to the popularity of the Transformer architecture in fields like NLP, optimization of Transformers is a rapidly evolving subject. For an impression of inference optimization, see this post by Lilian Weng.

Limitations

- Most studies cited here evaluate CNNs and ViTs on image classification, most commonly on ImageNet. This is not representative of other tasks such as dense prediction.

- Many comparison studies compare ViTs to ResNet variants, such as BiT. This is perhaps not an entirely fair comparison, since there are more recent CNN architectures such as RegNet and ConvNeXt.

Summary and Recommendations

The decision tree at the top of this page should provide a useful guideline for choosing a model based on various considerations. Based on the data discussed above, here is a summary of my recommendations for choosing between CNNs and ViTs.

- Transfer learning from a pretrained model should be the preferred choice 95% of the time. This holds for both CNNs and ViTs and is especially true when working with small or mid-sized datasets.

- Pick a pretrained model checkpoint with the highest upstream performance. CNNs and ViTs both transfer well, which means that the decision between the two architectures should be made by picking the model that performs best during pretraining.

- Pick a model checkpoint trained on more upstream data. This holds for both CNNs and ViTs. For example, pick a model trained on ImageNet-21k instead of ImageNet-1k, or a model trained on a large unlabeled dataset in a self-supervised way.

- Pick the largest model that fits your hardware and latency limitations. This holds for both CNNs and ViTs. Larger models outperform smaller models when trained on sufficient data, and transfer performance correlates highly with pretraining performance. An exception would be when your target task is simple enough not to require a large model.

- Prefer CNN if development time is an important factor. CNNs are a more mature architecture than ViTs, which can make it easier to work with due to existing frameworks and training recipes that are tried and tested.

- Prefer CNN for embedded and real-time applications. This is because there is a more mature ecosystem of tools available for CNNs.

- Prefer CNN on tasks where pretrained checkpoints are not available, or when checkpoints pretrained on datasets larger than ImageNet-1k are not available. CNNs are the best choice when large scale pretraining is not an option.

- Prefer ViT if robustness to image corruptions and/or data drift is a concern. ViTs have been shown to be relatively robust to such perturbations, possibly because ViTs are biased towards shapes, whereas CNNs are biased towards local textures and backgrounds.

- When using a CNN, consider using a modern CNN architecture such as ConvNeXt

- Consider trying out modified ViT architectures:

- Hybrid CNN/ViT architecture

- ViT with vision priors, to reduce the risk of overfitting. See, e.g., Swin and its derivatives

If I were to summarize all this in a few sentences, I would say that CNNs are a practical and high-performing choice for many real-world applications. For the most part, ViTs are worth trying if you want to try and squeeze out maximal performance. Also, Vision Transformers are worth keeping an eye on due to developments in self-supervised learning and multi-modal training, where the flexibility of the Transformer architecture is quite useful.

Finally, I have omitted a more in-depth discussion on applying ViT for dense prediction tasks such as object detection and instance segmentation. This comes with several caveats, especially when it comes to pretraining. I might write a part 2 of this post at some point where I discuss these things in more depth.

References

[1] Vaswani et al. “Attention Is All You Need”, 2017.

[2] Dosovitskiy et al. “An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale”, 2020.

[3] Steiner et al. “How to train your ViT? Data, Augmentation, and Regularization in Vision Transformers”, 2021.

[4] Kolesnikov et al. “Big Transfer (BiT): General Visual Representation Learning”, 2019.

[5] Touvron et al. “Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention”, 2020.

[6] He et al. “Rethinking ImageNet Pre-training”, 2018.

[7] Kornblith et al. “Do Better ImageNet Models Transfer Better?”, 2018.

[8] Raghu et al. “Transfusion: Understanding Transfer Learning for Medical Imaging”, 2019.

[9] Zhou et al. “ConvNets vs. Transformers: Whose Visual Representations are More Transferable?”, 2021.

[10] Naseer et al. “Intriguing Properties of Vision Transformers”, 2021.

[11] Zhai et al. “Scaling Vision Transformers”, 2021.

[12] Paul et al. “Vision Transformers are Robust Learners”, 2021.

[13] Xie et al. “SegFormer: Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers”, 2021.

[14] Zhou et al. “Understanding The Robustness in Vision Transformers”, 2022.

[15] Shao et al. “On the Adversarial Robustness of Vision Transformers”, 2021.

[16] Zhang et al. “Delving Deep into the Generalization of Vision Transformers under Distribution Shifts”, 2021.

[17] Bai et al. “Are Transformers More Robust Than CNNs?”, 2021.

[18] Liu et al. “A ConvNet for the 2020s”, 2022.

[19] Pinto et al. “An Impartial Take to the CNN vs Transformer Robustness Contest”, 2022.